So, today was another tiyul day. My school is being really good to us on that front, really trying to help us take advantage of being here. This was the trip North to go chase after Tanaaitic history. (The Tanaaim are the guys, more or less, that the Mishnah is quoting. The Mishnah is Judaism’s oral legal tradition, the foundation-piece for the Talmud and all subsequent Jewish law, and was written down ca. 200C.E.).

Our first stop was Ceasaria, which was the Roman capital of this chunk of land when they were ruling things. To get us pumped for the era, our guide played a scene from that Russell Crowe movie Gladiator, which was totally amusing at first and then just started to feel… well, disgusting and bloody. I’ve never been one for violent movies, and even more so over the years, I can’t quite fathom the point. We derive entertainment from watching a simulated version of people hurting other people? This is fun because why?

Then we got to Ceasaria. It’s a cool place to walk around–pretty seaside town with lots of old stuff.

Enough of the ruins are still extant that you can get a sense of the town-like feel, and there are signs indicating where, say, the vomitorium was (in case you need one, I guess). They have a classical Roman theater that used to be perfect (you know, say something in a whisper on the stage and you can hear it from the furthest seat) but it seems that people doing reconstruction work messed up the acoustics some. Now bands like Jethro Tull come to play there, adding further proof to the fact that this is quite possibly the weirdest country ever. That was all fun and good. Then we got to the next part of the ruins. More seats, looking down on a wide open space.

A didactic label indicated that this was once the site of chariot races. So for the first few moments I was excited about the place (Dude! Chariot races! etc.)

But then through the guide’s explanations (the guide, overall, was great) it became clear that this was only for charioteering later–earlier, and for a long time, this was in fact where the gladiator battles took place. Then he talked a bit about what that meant; I knew most of this, but it was good to put all the information together. This was the place where a lot of people–Christians, slaves, political prisoners, etc–were forced into bloody situations with carnivorious animals, Roman soldiers or each other, and killed in gruesome ways. For the entertainment of those in the stadium–fun to watch people hurt each other, suffer, and die painful deaths. At some point the demand for fresh blood was so great that the Romans were going to war just to have some capitves to thrust in the ring. Part of the entertainment was straight old-fahioned executions. And, of course, lots and lots of Jews were martyred there, too. Probably this is where the famous 10 martyrdoms in the Yom Kippur service took place. (Today we took a look at the story of R. Akiva’s flesh being torn with hot combs and R. Yishmael being scalped alive. For those of you who don’t know the other stories, they’re all at least as horrible.) Thousands and thousands of people were murdered in the space where we were standing. And as the guide talked, I noticed that I was feeling it.

Some places are charged with certain energy. At the kotel, the Wailing Wall, there’s a certain strong powerful force in the space. It’s right up close at the wall, and when I went up to the Dome of the Rock when I was here 5 years ago (pre-Intifada) it felt a little bit like walking through water, the air was so thick with… well, this juice, this juju, whatever you wanna call it. And whether that’s because the place has an intrinsic power, I can’t say, but it’s certainly the case that 3000 years of people directing a certain kind of intention (kavvanah) and energy there and offering sacrifices there and praying there and doing all of one’s holiest rituals there and, you know, Jews davvening in that direction 3 times a day (etc.)–it leaves something there, in the space. Of course it’s powerful.

And standing on the space where thousands of people were murdered, for their beliefs (sometimes) and for other people’s entertainment (all the time)–well, that space has a charge too. All that suffering and pain, how could it not? So unlike the Wall juju, this stuff had a distinctly negative, strong, tameh (impure) vibe. It was really affecting me. I felt like I could feel all of the people who were in pain and died there.

This being not an entirely pleasant feeling, I would have been fine with moving along. And regardless, it doesn’t feel entirely respectful to me to be standing around casually chatting on a space where so many people died, though as my friend Nelly pointed out, it could be a sort of a tikkun (healing) for the place that we were standing there learning Torah. Still. We stood there too long, and lingered too long, and then finally it was time to move on to the next thing and I was so moved and haunted by just being there that I just had to stand there for a moment longer, take it all in. Finally, I said the El Male Rachamim (the prayer for the souls of those who have died) because it was the only thing I could think to do–to ask God to take care of those who already paid their lives where I was standing.

Then I had to go wash my hands in the Mediterranean, which is one way to get rid of the gook that was clinging to me. That helped some.

Ceasaria after that seemed characterized, for me, as a place really, really without a heart.

We then, from Cesaria, went to Beit Sharim, which is understood to be (historically and archeologically speaking) where R. Yehuda HaNasi, the redactor of the Mishnah that we use, was buried.

Rebbi, as we call him, was a pretty major guy. Going to see his grave was, frankly, neat. And not surprisingly the place didn’t reek of stink the way it did where the murders happened. I mean, I’ve felt very very strong juju in the room with people who are near death or dying, and I sometimes feel it to a lesser extent in graveyards too, but…. well, it’s not always of that strongly negative tameh feeling like I was feeling so so so strongly at the gladiator field. Different kinds of juice, depending on what’s going on.

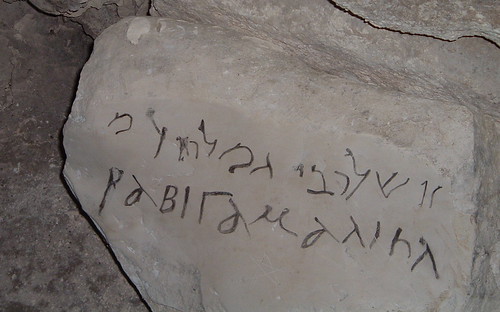

Beit Sharim is a beautiful little spot up in the green of the Galilee. It seems that Rabban Gamliel

and R. Shimon

are also buried there. Inscriptions on rocks and everything–supercool. When you spend as much time with these guys as I do (and anyone else who learns Rabbinic texts does), there’s a certain kind of special kinship you feel with them. They are, in a way, like friends, or teachers, or colleagues. Unlike Biblical figures, I feel like I have a fuller sense of who they were, how they lived, how they treated their wives, what their quirks and issues and personalities and strengths were, what they did on a Thursday afternoon, etc. Bible commentators can make up some of this stuff re: Moshe or whoever, but it’s not the same, and doesn’t feel nearly as grounded in actual historical reality the way the Rabbis do. (This is not to say that I don’t love studying the Bible! But visiting the site that they say is the grave of, say, Habbakuk, wouldn’t have me geeking this hard.)

Also, I would like to make official my wish to follow in the steps of Rebbi and have a beit midrash above my gravesite. Dang cool.

From there we went to Tzippori, which is where Jewish tradition claims that Rebbi is buried, and where there are more neat 3rd Century happenings. We saw lots of mosaics there, including the beautiful “Mona Lisa of the Galilee,”

which is part of the living room floor of a fancy Roman mansion. They had a lot of stuff going on for Dionysus there.

(Also got to see the mosaic of the Roman mansion’s loo–the tilework spells out “Health” in Greek.)

Davvened mincha in a 4th c. synagogue that a big honkin’ Zodiac in the middle of the beautiful mosaic floor, with what was presumably God as the sun in the center.

(Avodah Zarah, Shmavodah Zarah).

Then we went over to the pagan side of town and saw Amazons

and a centaur holding a sign that said, “I am a useful god,”

and then it was time to go home.

So here’s what gets me. After all this, a few of my classmates ask the guide if we can watch all of Gladiator on the way back. I mean, I get their logic (long day = movie) but… but. It just felt so disrespectful to all the people for whom these deaths were real, for whom the sport of watching people die wasn’t funny, glamorous, or sexy. To do the same thing that the Romans did (watch people get hurt for sport), just one step removed into glossy fantasy. Maybe when it’s more highly mediated one can feel like it’s not really happening and didn’t, to real people (and certainly not to people who were just like us). It’s an easy way to check out of the fact that, where we were just standing, “blood cries out from the ground.” (Gen 4: 10). I don’t care if my lack of interest in this particular film at this particular time makes me appear to others like an uptight prig. I was open as heck, and mimiced violence seemed a lot like… violence.

I hid in the back of the bus with my walkman on, reading a book, until we got back to Jerusalem.

Wow, that was one full day. I’m glad you saw some beautiful things to compensate for the tameh vibes, and as for praying mincha in the Tzippori synagogue – that must have rocked! I have the Mona Lisa of the Galilee as my computer wallpaper 🙂

Somehow I missed this post when it went live, but wanted to thank you for it. You really brought this day to life. Sitting here watching snow fall in western Massachusetts, where you are and what you’re doing seems like another world…

I empathize, too, with feeling the weird juju of that killing place (and wishing everyone else “got” it and would choose to move the hell on).

I tend to assume that places don’t have inherent juju; we mark then with our kavvanot and our actions. So I’m not sure the Kotel was inherently holy when it was built; I think it became that way thanks to us. Maybe this is another manifestation of my inherent egalitarianism — I’m reluctant to think that any one place is holier than any other place, at its core, though I do think we can make one place holier than another (or more tamei than another) by how we treat it and what we do with it…